A report on the forced shutdown of a Mongolian-language newspaper and what it reveals about China’s wider suppression of Mongolian culture.

A Mongolian-language newspaper in Southern Mongolia has been forced to cease publishing— another urgent sign of the Chinese government’s escalating campaign to eliminate Mongolian language and identity. Independent media outlet Rhyming Chaos has released an in-depth field report detailing the pressures faced by the journalists, the censorship climate, and the political forces that pushed one of the last Mongolian-language newspapers into silence.

This article introduces that report to an international audience and aims to raise global awareness of the cultural erasure taking place under Chinese rule.

Key Points Featured in the Report

- Shutdown of a Mongolian-language newspaper under political pressure

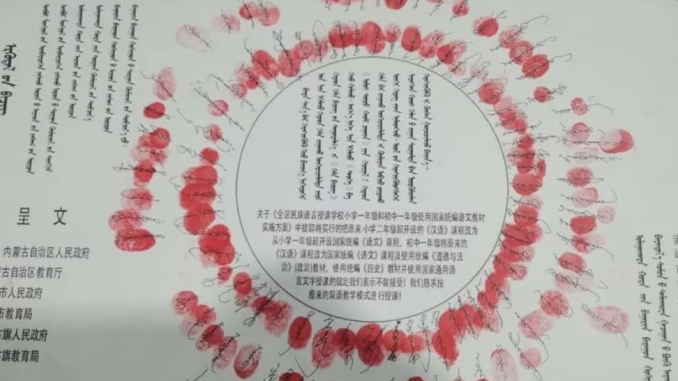

- Erosion of linguistic freedom following the 2020 “bilingual education reform”

- Intimidation of writers, editors, and educators preserving Mongolian identity

- Systematic dismantling of cultural and educational institutions

- Urgent need for international monitoring and solidarity

Why This Matters

For many Southern Mongolians, independent Mongolian-language publications served as a lifeline— preserving culture, transmitting identity, and resisting assimilation. The closure of this paper is not an isolated event; it is part of a long-running political campaign to reshape the region’s cultural landscape by force.

By presenting this report, the South Mongolia Kuriltai calls on the global community—journalists, human rights defenders, researchers, and all supporters of linguistic freedom—to pay attention and take action. Read the Full Report → About South Mongolia Kuriltai → Latest Human Rights Updates → Support Our Work →

This introductory article is part of the South Mongolia Kuriltai’s ongoing effort to document the erosion of Mongolian language, cultural identity, and civil rights under Chinese rule. More reports and testimonies will be published regularly.

I remember my father talking about my grandpa. They were living in a yurt, and they were wearing this stud, which is Mongolian ethnic clothes. And my grandpa is a hunter. He kills wolves. We actually have this mace thing, you know, this wooden stick, and at the end of it, there’s an iron ball on it.So my grandpa actually doesn’t use a gun. He rides the horses, and he… swing the mace and threw it to the wolf and the wolf got killed and a big dinner for the family.This is Rhyming Chaos, where we interview people who’ve lived through or studied times of great upheaval, tyranny, or authoritarian takeover. I’m Jeremy Goldkorn. I grew up in apartheid era, South Africa, just down the road from Elon Musk and lived in China for 20 years.And I’m coming to you today from my home in the heart of Red America, near Nashville, Tennessee. Today, my guest is Soyombo Borchki, a freelance journalist in New York. Soyombo is originally from Khorhat, Inner Mongolia, China, where he was a journalist with a state newspaper before coming to the United States.He recently published a piece with Equator, a promising new online magazine. It is subtitled, The Education and Re-education of a Mongolian Reporter. And we’re going to be talking about that piece today. Welcome to Rhyming Chaos, Soyombo.Thank you so much for inviting me, Jeremy. And thank you so much for reading the piece. I’m very grateful.Well, it was one of the most interesting, and to be honest, despite having a lot of grim content, most fun pieces I’ve read for a long time. May I just start, Sir, by making sure I’m pronouncing your surname correctly. Is it Borch Ginn?Yes, in Mongolia it’s Portuguese, so correct, yeah.Okay, so let’s talk a bit about your background. You know, your grandfather was an illiterate shepherd who kept dogs and ate wolf hearts and drank their blood for dinner. Your father became a professor and a prisoner at one point for pro-democracy activism in 1989. You’re now working as a freelance journalist in New York City.That is a really remarkable change over three generations. Can you fill in the context a little, talk a little about the Borchkin clan and your parents and your grandparents?Yeah, Borchkin is a big family name in southern Mongolia. We have a lot of Borchkins, if you met, means Mongolians in the region. And I remember my father talking about my grandpa. They were living in a yurt and they were wearing this döl, which is Mongolian ethnic clothes. And my grandpa is a hunter. He killed wolves.We actually have this mace thing, you know, this wooden stick. And at the other end of it, there’s an iron ball on it. So my grandpa actually doesn’t use a gun. He rides the horses and he swings the mace and threw it to the wolf and the wolf got killed. a big dinner for the family.And yeah, I tell this story to my American friends and they were like, what are you doing here? This is such a fantastic life. I think it actually is. And later I learned how to ride a horse. Actually during a reporting, I went tothe place where my grandpa lives in 2019, which is called Arfostum Banner, the Alu Kertensi. I was riding the horse and trying to interview the shepherds, and I met the old man. And I told him that my family is from this place. And he said, so your grandpa’s name is Otzer? I said, yeah.And he said, I’m actually your grandpa’s friend. So I get to interview one of my grandpa’s old friends. My grandpa passed away when I was seven, so I didn’t really know much about him. And it was very remarkable because I grew up in the city. I grew up in Hukot.Imagine that I grew up in the Inner Mongolia University campus. I don’t really know about how rural Mongolians live. I have this idea, I have this stereotype from movies or books, but I never really slept in a year riding the horses and see how this nomadic life goes until I had this reporting trip in 2019.I followed the shepherds for seven days. So it was very, very interesting.Wow. Did you feel as though you were somehow returning to your roots or did it feel completely strange to you?It was so strange because horses are very elegant animals. They have this 180 degree of vision and they can observe you when you’re riding them and They know you can’t really ride a horse. And that horse, I’m not much of a good rider. And it just started running very fast. And I was almost chopped from the horse.It was very hard to control it. But I ride the horse from 6 a.m. until like… 6 p.m. the whole day. And it was fun. And it’s really nice to see animals on the grassland. There are all kinds of cows, sheep, horses, and people sometimes driving SUVs because they are modern shepherds.Not many of them ride horses, only old people. But for me, it’s a really fancy thing.Yeah, yeah, yeah. Well, I’m glad to hear that a Mongolian’s horsemanship is probably not much better than mine. So that makes me feel good. You talk about Southern Mongolia. Could you explain that? Because obviously the province, the Chinese government refers to the official name as Inner Mongolia.Yeah, the region I came from is Southern Mongolia because the authentic Mongolian pronunciation literally would be Obur-Mongol. Oburu. means the southern side of the Gobi Desert. We call the independent country of Mongolia as Ar-Mongol. Ar-Mongol means the northern side of the Gobinders. But the Chinese authorities call our region as Nei-Mongol. Nei means the inner.So this Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region is a translation of the Chinese text, right? So it is hard to explain to English-speaking audience because Inner Mongolia means inside of Mongolia. And every time I say I come from Inner Mongolia, people would be like, oh, so you are from the country. But actually not.The Inner Mongolia means inside of China.For a person from the country of Mongolia, you’re actually from Outer Mongolia.Actually, exactly. I think there was a document in 1920s that the U.S. presidents were calling our region as Outer Mongolia and the independent country as the Inner Mongolia. That is very accurate, actually.But yeah, the Chinese use is different. I mean, I know even traveling around, not just Inner Mongolia, but well, Southern Mongolia, you know, your homeland, but Xinjiang and Gansu and those areas, people talk about like Konei or inside the wall or the Neidi, inside country, and they’re referring to the sort of central Han lands as inside.Exactly. The real border between the Chinese and Mongolian people is the Great Wall. The Great Wall is the actual historical border of two nations. And, you know, the Great Wall is a defense project that is to defend the northern nomadic cultures. And another function of the Great Wall is to prevent the people from the Chinesenation to escape to the northern territory. Once you enter the Northern Territory, you’ve got access to the Inner Asia. You can ride the horse, go all across the Inner Asia to the European lands. So this Inner Asia concept and Great Wall is actually very interesting in historical studies.So tell me a little bit about your schooling, your high school and your university education.I went to all Mongolian education from kindergarten to college. I went to Hukot Mongolian kindergarten. And then I went to Hengen Jama Ethnic Primary School, which is a Mongolian primary school. And then I went to Affiliated Middle School of Inner Mongolia Normal University, which is also a Mongolian middle school.And then I went to Inner Mongolia University’s anthropology studies. That is all conducted in Mongolian. So only one class is instructed in Chinese, which is the English lesson, the English class, because we don’t have that much Mongolian speaking English to teach the students English. So mainly that’s the Chinese.And also, of course, the Chinese class is instructed in Chinese.Which you had to do. Wow. Yeah. So how unusual was that in Inner Mongolia to have an education sort of from primary through tertiary education, almost all in Mongolian language for your generation?For my generation, it’s very rare because I remember in primary school, we only had 29 students in one class. And that is a very small number in China. In China, Usually a primary school class often have more than 60 students in one class. And we had 29.I actually wondered to have a student because we only sit in one row. We sit by ourselves. Like individually. I wondered when can I have a, you know, same desk friend. Do you know what I mean?Yeah.Yeah.So growing up, did you feel like you were like really unusual and that like kids in your neighborhood went to kind of ordinary schools and you were at like a kind of slightly strange school or did you not notice that?That’s a very good question because after I came to the United States, I had this idea of people who speak different languages. How do they interact with each other? How do they make friends? And actually growing up, I don’t have that much Chinese friends because we go to different schools. But I do have some Chinese friends.We play in the weekends. That is very rare. And for us, it’s kind of hard to find Mongolian-speaking individuals in Khokhot, which is the capital of Indo-Mongolian Autonomous Region. And our teachers would be upset if we speak Chinese during the class or after school. And there are some kids who went to Chinese schools, Mongolian kids.After they grew up, they always, not always, sometimes blame their parents for not taking them to the Mongolian schools because somehow I think after growing up, they realized their identity is so different from Chinese.Right. Now, but your parents were intellectuals. I mean, despite the fact that your grandfather was a wolf hunter, your dad was a professor at university and your mother was a journalist and obviously both quite thoughtful people who thought carefully about your education and steered you on this path.Can you talk about your parents a little bit and maybe a little bit about the trouble your dad got into 1989?Yeah, actually, he never really spoke to me directly about this thing. That’s why when I read Professor Stella’s book, The Force of Things, he mentioned how he discovered his family history in those letters, diaries. I discovered my father’s story in my mom’s diaries. She put the diary on the bookshelf.When I was little, we don’t have internet anymore. I don’t get to watch TV often. So what do I do? I look through the bookshelves to read. And I found a diary. There are letters exchanging. When my father was in the jail, my mom was writing something like, our son is doing better and better.You don’t have to worry too much. And my father’s diary was about something like, Today, I did this and that, but another Chinese guy from this cell hit me on the head. So something like that. So I never really asked them about what really happened.In our country, it’s kind of not comfortable talking about this kind of stuff.Yeah. I mean, I think that Mongolian culture is obviously quite similar to Chinese culture in that regard. I know a lot of Chinese people who’ve been through similar traumas and you just don’t talk about it at home.Yeah, I think it’s not a similarity of culture. I think it’s a big trauma that the Chinese Communist Party had on its people, especially, you know, after Cultural Revolution, the purge on the Mongolian people. There were actually, you know, 100,000 Mongolians died during Cultural Revolution. There is a book about it called The No Tombs on the Grassland.that the Chinese Communist Party tried to purge Mongolians who got professional studies from the Manchuria state, you know, created by the imperial Japanese. When I grew up, a lot of professors in the Mongolia University talk about this cultural revolution and you can feel their fear.They would automatically turn their volume down and they would whisper in your ear, like, you know, this and that happened during Cultural Revolution. And after I worked in Indian Mongolia Life Weekly or Indian Mongolia Daily, there’s also autobiographies of the old journalists. They were talking about how Mongolian and Chinese relationship changed during the Cultural Revolution.People got really serious. People got really… And so these traumatical events, I think, made us less likely to talk about family histories and how terrifying it could be, the state could be.And how do you feel about, I mean, you’ve just published a piece that sort of lays bare some of this family history. Did you make a decision that silence was no longer worth it or that you feel that there is something to be gained? I mean, obviously it’s fascinating for us, for the reader, but for yourself,was there something to be gained in telling these stories? And do you worry about backlash against your family?First, I always thought about this story because since the re-education happened, I always thought about I should make something of it because I feel like we didn’t really write so much about ourselves after Cultural Revolution. We don’t really have an accurate document on what happened to Mongolians after 1949, after 1976, after 1981 protests, after 2011 protests.And another thing is I always told my story to my American friends here, and they were like, wow, you really should write about this. This is so interesting. This is so fascinating. And they constantly encouraged me to speak up and I was very inspired, I guess. But the process was, you know,it’s not that happy because I always constantly, you know, fearing that it could make my family into deeper trouble. And it’s always hard to speak up as someone who grew up in China to talk about national politics, ethnic politics. And I met a lot of Mongolians in diaspora communities here. Some of them came hereyou know, with only $10 in their pocket. And they still advocate for Mongolian rights and indigenous people’s rights, not only in politics, but also in community building. And I think I learned something from them that is, it’s really important to speak up, especially after you came to America, because this is a place you have this press freedom,freedom of expression, The question really looming over my head, I think, is that now I have this freedom of expression. Now, what am I going to do about it? Am I going to be silent and sit still or just say something about it? And I think the best story…would be myself because it’s very hard to interview southern mongolians about this incident most people would be very afraid they would be like can you not use my name can you just blur out my voices i understand that it actually reveals how terrifying it is but also i think from a human existence perspective thatthese documents, this kind of writing is very important. And of course, also entertaining. And another thing I think is that when I was in China, there’s a magazine called People’s Magazine, and they wrote the piece about how Uber ended in 2016 or 2017. I don’t remember the year,but the article was about how Uber employees were crying after they got defeated by the DD company. And I’m always fascinated about these kind of stories about ending, these kind of stories about cancellations, these kind of stories about… something came to an end. After this re-education happened, my wife was always saying that,now you have your own Uber story. Your publication is ended. I was like, yeah.Right. I have to tell you, as somebody who’s been in China-related media for a long time, I have a lot of endings. Media, it’s sadly a common story. But let’s talk a little bit about then Inner Mongolia Daily, where your mother worked. And then after college,you worked at a construction site and then a kind of sketchy travel company. And then in 2014, you You got a job at the Inner Mongolia Life Weekly, partly, as you write, as a result of your mother’s employment at the party newspaper, the Inner Mongolia Daily. So could you describe exactly what the Inner Mongolia Life Weekly was?We have 17 steps, six editors, two art editors, one editor-in-chief and one wise editor-in-chief. And another one is the administrator of the office. All of them, except me, is coming from the rural part of southern Mongolia. kinds of privileges, including speaking English. So when I first started there, you know, there’s a strange feeling of, well,you are a privileged kid. You grew up in Hohat. You read different stuff. You use VPN. You watch YouTube. We’re just doing this shepherd story, okay? So it was very hard. I think I used at least one ear to gain their trust. They were like, oh, this guy signed…It’s actually a Mongolian kid, a genuine, authentic Mongolian kid, just like us. And we were really in a good relationship until 2020, when the newspaper got shut down. They were in tears. They were literally crying. And I remember we went to a restaurant for lunch, all of us.We were just like the last dinner or the last lunch.The last supper, right.Last supper, yeah.I still remember that. I mean, it must have been so sad. So in the Mongolia Life Weekly, this was sort of modeled on other similarly named publications elsewhere throughout the country. And it was, I guess, an outgrowth of the somewhat more liberal approach to media. I guess it was partly an outgrowth of the somewhat more liberal approach.to media of the Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao eras, when for a lot of state publications, making money actually became more important than ideological rigor. I was working a lot in Chinese media around that time, and it was pretty wild times. And you discuss… Some of them, I mean, some of it, I think,has a real inner Mongolian bent, such as the drinking culture. But there’s also, because of the commercial incentives, there was this idea that you should, in fact, publish stories that were interesting. And I think you managed to do some. I mean, you did… pieces on the Iron Maidens,the Iron Girls who’d been mobilized to hard labor during the Cultural Revolution. You did a piece on an enforcer of the one-child policy who conducted forced abortions on pregnant women, things that I don’t think would be possible today. Can you talk a little bit about working there and how you managed tosort of avoid being completely drunk all the time and avoid the censorship and still manage to publish some interesting work?It’s a very good question. I think I was, generally speaking, I was very fascinated by stories, long-form stories, feature writings. I grew up reading the South China Weekly, South China Weekly, and… Nanfang Zhou Mo. Nanfang Zhou Mo, yeah. You know, Li Hai Peng… He created another feature writing thing called One Lab.And he wrote about how this ship mutiny happened on the Pacific Sea. How… Yeah, a lot of interesting stories. And there’s no way to avoid drinking if you work in the… system or propaganda system because this is the culture and everyone drinks. It’s not because they like to drink, I guess.It shows how you respect your superiors, how you respect your editors. There are a lot of tacit knowledge in China that If you work in the doorway system, you don’t get to sit on the chair fully. You sit one third of it. When you make a toast, you don’t just toast.You have to lower your cup to other person that you are toasting to show respect. You have to listen to what people talk. Like if our editor-in-chief gives a speech during the banquet, we sit on this round table, right? So everyone drinks coffee. There’s this thing, like, he makes the toast first, and then it’s not your turn,the wise editor’s turn, and then the senior journalist’s turn, and then the junior journalist, and then it’s my turn. And when it comes to my turn, I have to give a speech, like, it would be carefully said, make sure nothing, you know, sensitive, of course.But by this time, you’ve already had a few shots of Baidu.Yes, this is not only shots, this is the Fenjiuchi, you know the Fenjiuchi?Right, the flagon. I don’t know what you’d call it in English. A jar.Yeah. So you have to take the jar. And that’s how you respect the party staffs who are sitting right across you. And they will be very pleased.Well, you did do interesting stories. You know, you managed to meet some interesting people and, you know, some on subjects that are, you know, even at the time were quite sensitive. So, I mean, I’m particularly thinking of your profile of an enforcer of the one-child policy who conducted forced abortions.So how were you able to get stories like that published? Was it a question of emphasis, how you introduced the story that you’re not actually… the purported nature of the story isn’t to criticize the one-child policy. You’re just telling a story of a person who worked in the system.Or, you know, how do you massage a story like that so that it can get past the census? Which even in the relatively liberal times of the 2000s, the flourishing of Nanfang Zhou Mu, I mean, is still very strictly controlled, right?Yeah. When you go to interview trips, you first report to the propaganda minister of the local region. Like if I go to interview in Hohot, I have to report to the propaganda department in And then I will tell them what I’m planning to report.And they actually have a list of the topics that they want you to interview, like economic development of the region or the party development, party construction of the region, that how many new party members they have this year. And you will, now that’s the time you got to improvise.You will say, okay, I will report the A, C, and D of this list. And can I also interview this subject that I know a person who went to Korean War, who is a Mongolian. I think his story is very interesting. How about that? And he will be like, well, okay,we will get you a jeep and you can go to this remote place to interview him. And then, of course, there’s a forced abortion enforcer. I remember he’s a party secretary, retired party secretary of the Otis region. And I didn’t interview him because of the forced abortion.He said he mentioned himself that a lot of local people are criticizing him for the forced abortion that he conducted during the 1980s to 1990s. So I thought that was a very interesting perspective. And nobody said, I can’t interview that. Meanwhile, the propaganda staff is standing in the same room that you are interviewing.Every time they must be there, they drink with you, they eat with you. And when you conduct interviews, they will be standing in the room, I think, to see what questions you are asking. But if the guy said himself, I think it’s very natural for you to ask continuing. So how do you… identify who’s pregnant.How do you conduct this kind of operation? And yeah, this guy, this enforcer, he become an alcoholic. And when we interviewed him, we already drink one bottle of Baizu. And that’s the only way to get them talking. Because in this, our region, people don’t really talk straightforward to strangers.It’s very hard to interview them, even if you are a state-regulated journalist. So You drink with them, you make friends with them. And then I wrote this article mainly about abortion. And my editor in China was like, well, now you wrote about this article. And well, but by that time,I think China haven’t said the one child policies should not be canceled or they never had this population crisis in the public discourse, I guess. So it was okay to write about it. And after all, it’s a Mongolian publication. Nobody really reads about it.So my father’s take was that he said the Indian Mongolia daily is too dirty to put the bread on it and make it a pack and too hard to wipe your ass. So nobody reads it, his idea is that.Yeah, that is certainly often in China. I think you can get away with interesting things if they’re small and nobody pays attention. Can you talk a little bit more about the sort of commercial culture at Inner Mongolia Life Weekly or at the daily Inner Mongolia Daily? I mean, I’m quite familiar with that structure.It’s replicated in every city and sort of provincial center around the country where the party newspaper is the dailies. Beijing Rubau is the Beijing party branch newspaper. And then it’s not only the newspaper, they also have a bunch of other stuff, you know, even after the… economic reforms in the 1980s,they still tend to own a lot of property, real estate, and the Dunway, the work unit might even have a hospital, you know, other things attached to it. And that obviously is very fertile ground for corruption, some of which you talk about in your piece for Equator.Can you describe sort of how the commercial incentives works and the corrupt boss of the Inner Mongolia daily and his fall?Yeah, of course, there’s a lot of benefits if you can have a job in the state-affiliated businesses. It’s generally called Danwei. And another thing is that we don’t have a Benzhi. We are not officially recognized as a Danwei, the Southern Mongolia Love Weekly. So my mom always said we are the kids from the stepmom. So we’re…not really fairly treated. The Indomomolet daily is state-related, very much state-related, and all of the staffs have the state benefits And for Indian Mongolia, South Mongolia Life Weekly, we don’t have this. It’s interesting. And commercially, we have living complexes. If you step up to Indian Mongolia daily, you can have an apartment. Not free.After 1996, I guess, you have to pay some money. And then another would be, of course, you have a medical plan. You have… Actually, I think the salary for Danwei system, the state-affiliated system, is actually some allowance money you get to spend. All of the other spending in life is already covered by the state.So it’s a good deal if you’re in the system. Yeah. In 1980s, you know, people say, which means the one who makes egg on the street makes more than the rocket scientist. So it’s a complaint made by the state-affiliated staffs that they think the salary is so low comparing to individual business owners.Because actually the salary for the state-affiliated business, state-affiliated staffs is actually a small amount of money comparing to what you already got from the system.Right. But if you’re at the top of it, like your original editor-in-chief, you actually have an ability to move money around because you’re in charge of state-owned assets and you can skim off the top. So what was the boss doing at the Inner Mongolia Daily not too long after you arrived? You mean the murder case? Well, yeah.Yeah. That led to the murder case. Yeah.Yeah, his name is Liu Jinghai. He got arrested, I think, in 2015, January 2015, I guess, because he appointed his nephew in this Wu Ye Gongsi, which is a real estate service company.Property management, I guess you’d say, yeah.Yeah, but his nephew withheld salaries from the maintenance worker, and this worker… Yeah, killed Liu Jinghai’s nephew with an axe and made the investigation leads to Liu Jinghai again. And Liu Jinghai is quite unpopular among Mongolian journalists because I remember there was one time the Inner Mongolia Daily got a 500 million yuan state fund to dothe propaganda, of course. And I’m sorry, the 600 million. And then they gave 550 million to the Chinese department and the 500,000 yuan to the Mongolian department. So of course, Mongolian journalists were underfunded, and they really didn’t like it. And if you see my Substance About page, I uploaded my press ID.You can see it says Southern Mongolian Life Weekly, and then it says Mongolian edition. This ethnic label saying that Mongolian edition, the word will make the propaganda officer notice that we are Mongolian journalists. We are going to write in Mongolian publications. So they don’t have to treat us that well as the Chinese journalists.So yeah, they will give us two cheaper wines and liquors during the banquets. So Mongolian journalists doesn’t really like Liu Jinghai. So that’s why when the investigation happened, people said firecrackers.But let’s complete the story. He’s corrupt, and one of the disgruntled employees murders him.His nephew. His nephew. Because he appointed his nephew in the company. And then police realized, oh, so you appointed your nephew in this state-of-lade business, and your nephew took the money from the maintenance guy, and then the maintenance guy killed his nephew. And then this is going to be Liu Jinghai’s responsibility.Wow. Yeah, what a mess. Your time at Inner Mongolia Life Weekly sort of was the tail end really of the sort of somewhat freer approach to media that characterized at least much of my time in China. And, you know, I think the end of the Inner Mongolia Life Weekly was partly about the end of easymoney for commercial media, for state publications, and the end of a certain experimentation of media in China. But there was also something else going on at the same time, which was a complete change in the so-called ethnic minority policies in China, where basically post-1949, the People’s Republic hadadopted a version of the Soviet model where there was this idea that recognized ethnic minorities would be encouraged to learn their own languages and maintain their own culture as long as they agreed to be part of a greater Chinese nation. And that idea in the 2010s started to be challenged inside the Chinese government and then, you know,I think you saw the sort of hard edge of the change of that policy. So when did you first start to become aware that Mongolian was going to be under threat, the Mongolian language and Mongolian identity?It was April 2020. It was during COVID. We were still panicked about COVID during the time. And there’s an organization called Minru Cu Jinghui, a pseudo-democratic affiliation of the Chinese Communist Party. literally meaning promoting democracy or organization. It said some local institutions, some local legislative regulated that Mongolian ethnic languages should be theinstruction of tool in the local schools, which violates the constitution of China. They published an article. So, of course, Xinjiang is doing no Uyghur education anymore. Tibet is doing no more Tibetan language education anymore. So who’s left? It’s us. Everybody knows instantly. And we were talking about this in our Southern Mongolia Live Weekly editorial room.We were talking about, is this really going to be a thing? Is this really going to happen? By that time, I still wondering maybe… They won’t do it because by that time, I really don’t know much about politics or in general, like how China’s ethnic policy changed from the communist ideal mode to nation state mode.But right now, I carry this question with me in New York. I really want to know how come I received re-education from the Chinese Communist Party and then I realized China is not a nation state like most countries in the world. Like if you find a Northeastern, a Dongbei people and a Hong Konger, and let them speak,they don’t even speak the same language. One speak Cantonese, another speak Dongbeihua, the Northeastern language. And even in Hu Hu, the Chinese people, the so-called Chinese people, they actually speak Shanxihua, the Citihua. Citihua is very different from Putonghua. Putonghua is Mandarin Chinese. It’s an artificial language promoted by the CCP propaganda system, only speaking in the CCTV.Nobody really speaking Putonghua in China. Actually, If you visit Chinese family in Hohot, and if a kid goes to university and starts speaking Putonghua in their Hohot family, the Chinese parents would be very upset because, oh, now you got educated. Now you’re speaking different dialects than us.Mongolians were really wondering, will this policy really be implemented in September? And people were having a lot of confusion because there were no official announcements. There were no Hongto Wenjian, the redhead paper with seals. There were no explanation. There were just rumors, rumors everywhere about this party official said this, or Bu Xiaolin said that,or Shi Taifeng said that. Shi Taifeng is the party secretary officer in the Mongolia Autonomous Region in 2020, who is now the organizational department head in the CCP right now. So we really wanted an answer in 2020, I guess. that whether CCP is serious about this,are we going to really lose the ethnic language instruction mode in schools? Because for me, it’s like the loss of my childhood. I grew up as a Mongolian in the Mongolian schools. And if the school doesn’t teach Mongolians anymore, then where am I going to find these kinds of memories in local schools?Yeah, that’s very sad. To leave China for a little bit, when we were talking on the phone the other day, you talked about going to a gathering of Mongolians, of exiles or emigrant Mongolians in the United States from all different countries. Could you tell us a little bit about that? Because it seems your experience, I mean,it has its own particular Chinese angle to it, but you actually have a lot of things in common with ethnic Mongolians from other countries.Yeah, we have Buryak Mongolians and Kalbic Mongolians who live in Russian Federation. We have Khazara Mongolians from Afghanistan. We have, of course, we, the Southern Mongolian from China, and also Towa Mongolians, also the Mongolians from the independent country. So, In the United States, we have this thing called Mongolian-American Cultural Association, founded by Hangyeng Ganbojab,who is a right-hand man of Prince Dmchukdung-Rug. Prince Dmchukdung-Rug is the leader of the independence for the southern Mongolians since the early ages of the 20th century until the end of the Second World War. And this Henggunga Punjab came to United States and he realized that we shouldestablish some kind of cultural heritage for the Southern Mongolians or the Mongolian diaspora in general in the US. And he founded this Chinggis Khan ceremony. This year is the 38th anniversary of the Chinggis Khan ceremony. And all Mongolians living in the US came to this event in New Jersey. And I gave a speech.I’m very grateful to the opportunity also. And I realized that the Mongolians who’s from Russia, mostly speaking Russian, or a Russian dialect Mongolian, or not Russian dialect, but the Kalmic dialect or the Buryatv dialect. And we speak in Mongolian language also. And the Hazara Mongolians escaping from the Taliban came here also.And Russian Mongolians escaping Putin’s war because Putin is sending them to Ukraine war. And they become exiles here also. And we escaping the Chinese Communist Party in New Jersey. And hundreds of them, more than a hundred people gathered in this New Jersey event. And I realized English is the only communication language between most of usbecause people speak very different languages in that room.That is amazing. So to go back to China, so the message starts coming down. Mongolian is going to get eliminated from the classroom and from books and media. And there was a protest movement. And quite remarkable in some ways. Couples obtaining sham divorces so non-state employed parents could keep protestingchild and using the fact that you couldn’t actually write in Mongolian on WeChat so you’d take photos of Mongolian text and then use those, which allowed you to some extent to evade surveillance and censorship. Can you talk a little bit more about this type of creative resistance and the period around that and, you know,what’s happened since then? Is there still any kind of resistance to the new policies? Was that really, have people had to accept that this is the new reality?Yeah. During the protests, there were a lot of interesting things happened. I remember people were fundraising black shamanism, trying to find black shaman to curse Xi Jinping. They collected at least like 5,000 yuan to hire one black shaman to do black magic.It didn’t work.I guess Xi Jinping hired another powerful black magician to defend Xi Jinping. But it’s real. It was on Bino. It’s only Mongolian social app during that time. I think it was August 2020, before the Bino was shut down. I literally saw that. I was like, oh, these people were serious. And they were really collecting money.And they were advertising like this. Someone who is born on 16th of May. I think that’s 16th of May. I think that’s his birthday. I don’t quite remember. But they said, We are fundraising a black shaman event to curse someone who is born on 16th of May and someone who wears suits a lot.Some description like that, of course, not mentioning Xi Jinping. But I just realized, oh, they are going to curse him. And we have herdsmen raising the black banner. Black banner, the black street. June 15. June 15. I’m sorry. June 15. Yeah. So they also, they’re raising black banner, war banners.The white banner, white suit means peaceful for the Mongolian people. And the black banner means the Mongolian people at the event of war. This is where you summon Mongolian soldiers. And we have Mongolian wrestlers who refuse to wrestle anymore. We have artists refuse to sing anymore. 11 people committed suicide during the protest.Because you can’t take it anymore. And we have Mongolian police officers resigned from jobs. Mongolian banner, local governor. You know, it’s Xi, not Xi. Right. Banner, but not county. Banner.Yeah. The traditional Mongolian sort of way of dividing up areas of land instead of a county.Yeah. So they resigned from job. And also people creating all kinds of pictures. I really love this protest art. That’s what I witnessed. Not witnessed. That’s what I was observing in 2019 during the Hong Kong protest. I was really fascinated by… those symbols like umbrellas and for us it was also an umbrella or a shield that amother protecting their kids from the enemies that is a shield wielding mother so I was really fascinated and we also have our linen wall the small postcard we paste on the There’s a coffee shop in Hohot. People write in Mongolian saying that our mother tongue will be forever.It will never be eliminated, those kind of content and paste it on the wall. It’s just like Hong Kong protest. And I was very excited and also very depressed because they were really implementing the Chinese instruction. And I was really amazed by how creative we can be,even when I thought Mongolia are just some cultural people who only know to sing or to wrestle. But it’s actually not. When it comes to this kind of events, people got really sentimental and emotional. They got very creative. They wrote a lot of things. There are tons of songs, poems uploaded on WeChat or Loin.It’s very hard to find it on YouTube. But of course, delete it after that, after the protest. people creating songs, and they were singing the song, holding their kids, embracing the kids, and then uploading videos. And I think right now, on Chinese doing, if you are a user inside of China, especially if you are a minority,like a Mongolian, you cannot upload a singing video solo. You can upload a singing video if you are… having a dinner and everyone is having a party, it’s okay to sing and upload the video. But if you are singing by yourself, sitting in a room, that’s very sensitive and we won’t let you upload that.Wow. So they’re relying on the fact that if you’re in a room, you’re going to be restrained by social conventions and you’re not going to start singing about Mongolian independence or something, whereas on your own, you’re unpredictable. What do you think the logic is there?I think the idea is that if you’re having a party, you’re drinking, you’re eating, and you are singing, that’s much more like for entertainment. But if you are singing solo in your room, it’s more like a message that they don’t understand that they fear of. Because most Chinese people don’t speak Mongolian,so they would be very suspicious about what message you are trying to say. And you also mentioned what kind of protests we still have. We are, of course, still resisting the Chinese instruction, not in the public, of course, but we have secret homeschools that teach kids in Mongolian. Very touching.We have Mongolian textbooks printed in Japan because Chinese education department stopped printing Mongolian textbooks anymore. So the resistance hasn’t stopped. It’s a language, it’s our heritage. We can always teach to our next generations.It is something that you can, if you have a sufficient motivation, you can’t keep it alive without official support. That’s true. But at the end of this, as much as there may have been some hope and solidarity with other Mongolians in the protests, I mean, they largely proved to be ineffective in terms of actually stopping the newpolicies. And you, which provides the name of the article you published in Equator, you yourself were the subject of a re-education. program. You describe it as boring rather than scary. And I think that’s one of the fascinating things about your piece is that you reveal very clearly how authoritarianism in China works.And it’s not always the jackboot on your face. It’s often in more subtle and often more boring ways. But what was the re-education program that you had to do at Inner Mongolia Life Weekly?There’s a textbook that for every one of us. And I think since there’s a textbook, it cannot be printed only for our editorial. The re-education must be conducted in a broader sense. I think there must be a lot of students. And another thing is that we read and memorize the golden sentences. Golden sentences meansJinju, literally translating Jinju, means what Xi Jinping said is gold. And so it is golden sentence. So this textbook is edited like Bible or Quran or religious scripture, like verse one, chapter two, and sentence three, this kind of sequence. And there’s like Xi Jinping, on ethnic policies, Xi Jinping on economic development, and you got to read that.I think Chinese society is so, I don’t know the right English word, but I would say segregated because they don’t have zero knowledge towards Mongolia. They say we don’t speak Chinese. I speak excellent Chinese. All of us speak excellent Chinese because we were born and grew up there you can’t live without speaking or writing Chinese.And the teacher in this re-education program wanted us to speak in Putonghua, speak in Mandarin Chinese. I can do that. I can do it in the Hohot dialect also. And they want us to read aloud. And I remember the teacher said, you know why you need to learn Chinese and cancel this Mongolian education.We were like, no, we don’t know. They said, because the Mongolian language is so backward that they cannot express scientific terms. We were like, well, what do you mean? They said, because you don’t have words like physics or vocabularies in physics or chemistry. Like without Chinese, you can’t learn physics as chemistry or all STEM knowledges.And we were like, no, we have these physics terms. Actually, you know, called which means oxygen the literal translation of oxygen that the generating oxy or hydrogen we have this kind of vocabularies we have We can also do mathematics in Mongolian. We can count in Mongolian. And we’re not really believing it.They said, no, you have to learn this modernized Chinese to understand science. This is the point that they don’t understand because they think they are the modern kind of people and we are the backward kind of people. They are the scientific people and we are the indigenous people.We need to learn science or any other knowledge from Chinese. This is… I think this kind of thing, if someone speaking in English or in the U.S. saying to the indigenous people that you have to learn English to learn science, it will be very serious consequences in the U.S.Now, although, I mean, one has to admit, in very recent history in the United States and Canada and Australia and, you know, Other countries, you know, Denmark, Finland, you know, where there are indigenous populations, the approach has sometimes been quite similar in terms of forced assimilation with languages. Totally agree.But I mean, now it’s the 21st century. Yeah, we should have moved on. we should have moved on why are we being considered as some ignorant people who doesn’t know science only know herds or cows or ships or horses so that’s what i really didn’t like the part and it’s a very boring thing you know this downwaything everyone wants to be working in the downway actually it’s super boring you have to drink tons of badu and everyone is so boring you You know, these Communist Party members are boring. They don’t have this intellectual curiosity to explore things. They just want to have their monthly salaries.They are definitely not the communists coming from Europe in the early ages of the 20th century. They are the boring communist members. And also, I remember we had an exam at the end of the re-education. So there were no supervisors. And the goal of the exam, I guess, is to not expel anyone from this job.It’s just a showcase that everyone learned something from this re-education and now we can graduate. So we cheated with each other in this meeting room because there were no supervisors and everyone just had the exam. And we were asking and discussing the questions like, what did you select for the question one?And what’s the answer of the question two? But yeah, now I’m smiling and laughing, I think, saying it in a funny way. But during that time, I was really depressed. I really didn’t want to go, but people around me were saying something. Just follow their order and apply some university in the U.S. and stop being here.And also, I met some professors from International University. They were saying, again, they were turning down their volume, saying, the Cultural Revolution is coming. Okay, just go, just go. So I decided, yeah, why would I be re-educated? Yeah.I mean, I think it was good advice. And because it didn’t stop, I mean, after you left, you know, after that initial sort of attack on Mongolian language in schools and media, you’ve documented recently Mongolian schools being quietly renamed to remove the word Mongolian. And you’ve described it, I think, as the…removal of memory, identity, and cultural presence. Can you talk a little bit more about that, about what’s going on in Mongolia now in terms of this sort of ongoing campaign of, I think, the signification or cynicization is, you know, one of the words that is being used in China?Actually, during the 2020 process, we were already saying this. We were already discussing about what would happen if this policy fully implemented in Mongolian schools. We were saying things like Mongolian teachers would be relocated, reassigned. That’s true. Most of my Mongolian teachers from my high school or primary school,they become cafeteria teacher or the dorm room teacher now. And we were discussing about what would happen to Mongolian schools. There will be no longer Mongolian schools since the instruction would not be conducted in the Mongolian. So that would be Chinese school. And of course, according to the golden sentences of Xi Jinping, he said,we should promote the 민주 hundban, which means putting different ethnic groups, the Huns, the Chinese, with the Mongolians to be in one classroom. So, of course, if the language of instruction is changed to Chinese, what’s the point of keeping Mongolian kids in one school? And one thing is that international media shifted attention after 2020 protests.They don’t report it anymore. But I think there’s still, I at least, we the Mongolian in diaspora community, have this responsibility to document this history that things are quite happening. And there was one friend asked me recently about, what does it really mean that the renaming of the Mongolian school? I said, this is just,if I get to go back to Hohot today, I would not recognize my school anymore because the name has been changed. The school carries so much memories. That’s the place where I grew up and met all my friends and teachers. So it’s very sad. But still, it’s also showing…It’s a voice against the Chinese Communist Party saying that we are not surrendering. We will not be intimidated because things will be documented and you will be held accountable.Right. And I suppose… May I presume that that’s one of the things motivating you to write is accountability?I think so. And also, I think I was wondering why was I sent to re-education class when I first came here. And then I think the question shifted into how come I put myself in such a vulnerable position to the state without knowing it. Like, how come I call myself a journalist in Southern Mongolia Life Weekly?And then I didn’t observe this ethnic policy shift. I was reading New York Times, Wall Street Journal, watching YouTube. I know New Yorker. I read tons of Western media. But somehow, I think before 2020, I was just reading it as an English reading practice or… Just for fun, because long stories, feature writings has a lot of fun.And when it really becomes reality, I felt really bad. And I remember in September 2020, there was one Mongolian girl who’s planning to marry a Chinese man. And they canceled their wedding during the protest because they can’t marry with each other anymore. It creates so much chaos.They couldn’t marry. What exactly was preventing them?Because it was during the protest and a lot of Mongolians realized that the Chinese Communist Party and also the Chinese people doesn’t like us. It was until 2020 protest, I realized some of my Chinese friends actually told me that it’s actually a good thing for you, you know, it’s a… You guys should be educated in Chinese.And also in Colombia, I was discussing this in the Mongolia re-education thing. And one of the Chinese students I met at the party, he said, it’s actually the right thing. China is doing all the right thing, including Xinjiang, Tibet. I was like, why? Why would you say that? And he said,his father is working as the Xinjiang autonomous region in some level of this government. It’s an official. So, of course, it’s a good thing for them. And I realized during the 2020 protests that some Chinese, they never really being straightforward to me. when I was a friend before the protest.It’s okay for me to drink with them, breathe with them. But they never said their real feelings toward Mongolians until 2020. I mentioned this part in the Equida piece about how people suddenly turn into political animals, trying to say, you are actually wrong. I was like, oh no, this is just…So I’m very interested in these kind of things, that how people should be politically aware from the authoritarian government and how people should actually use the political knowledge to understand reality, understand what’s going on. News is just not some article written online or on paper. There’s actually real-time consequences.I think if there’s one lesson I can draw from it is that when a government starts targeting one vulnerable group, you may think it doesn’t matter because you’re not part of them or they’re a minority or maybe you think they’re backward and they should not ride horses andthey should work in a factory or whatever the justification is. But the oppression will come to your doorstep eventually.Yeah, but I’m fully aware of this, what’s going on in Xinjiang and Tibet. One of my friends works as a judge in Urumqi. He told me that he cannot resign anymore because they have their hukou in Xinjiang. The household registration is registered in Xinjiang forever. He cannot find other jobs in other provinces.He told me his director told him to sentence an Uyghur guy who uses VPN for nine years in jail just because he uses VPN. I’m aware of this. Also Tibetan schools, Xinjiang Re-education Camp. I remember reading Austin Ramsey’s Xinjiang document in New York Times when I was in Wuhan. I was like, wow, look at this Western journalism.This is so cool. This is what I want to read. But it’s so hard to… He explained that all of a sudden in 2020, you become the target.I hate to say that growing numbers of listeners around the world might come to recognize that sudden, horrible experience of realization. So Yombo, we’re pushing against time, but me, your journalism career and your life in Chokhat comes to an end, really. You come to America hoping for a fresh start.And here you’ve delivered Amazon packages where you actually did the famous peeing in a bottle experience to make sure that you could deliver them on time. You worked at a law firm where you were subjected to kind of crude stereotyping about Mongolians. And then you had some work at VOA.And unfortunately, you were doged when the funding was cut. So quite an interesting slice of life you’ve had here in the United States. How has your American experience compared to your expectations before you got here?Well, most of my impression about the US is coming from the Hollywood, I guess. I watched too much Al Pacino and Robert De Niro movies, I guess. Me too. Me too, before I got here. After I came here, U.S. is really interesting because I remember in Columbia, during the Columbia University,I remember one student doing yoga and the professor is like, nothing happened. But for someone who is coming from China, it’s just… So shocking. I had never seen students doing yoga during the class. And also, I remember it was my first Halloween here. I did all these reading materials, 200 pages, 300 pages in the library.And I took Subway home. It was 2 a.m. And then all of a sudden, a group of young men came in, you know. They have wings. They don’t have any clothes on. They only have wings. And they only have panties. I am the guy who had my backpack on and, you know, did my reading all night.I was like, what’s going on here? It’s like, so what’s going on? And I realized this Halloween, it’s a big thing. And I feel like, oh, look at me, a nerd. News is really interesting. I feel people are very friendly and also they are very serious about what they do. Not like Chinese that way.And I also remember when I got invited to a Columbia party. I realized people only drinking one bottle of beer the whole night. And it was my first time here. I was like, what’s going on? Why you guys don’t drink? I was so ready to drink.But now, after five years staying here, I don’t really drink that much. Occasionally, one bottle.Right, you’ve picked up the American sobriety.Remember, I’m eating bacon and eggs this morning.Yeah, we’re back to the breakfast. We started where we began. So what a fascinating chat. You know, I think I could talk to you for hours about this. And I wish you the best of luck here in the US and, you know, with your career. And please keep on writing. I mean…It’s so rare to get a look into your experiences in Mongolia. I mean, we have a lot of accounts of people who’ve worked at state media or gone through similar kinds of re-education in other parts of China, but it’s really unique to have it from a Mongolian perspective. Thank you so much for coming on Rhyming Chaos.Thank you so much for having me, and thank you for this opportunity.The Rhyming Chaos podcast is produced by Maria Repnikova and me, Jeremy Goldkorn. The show is edited by Kadra Scripts. The theme music is Paperboy, composed and performed on the Guzheng by Wu Fei. Our closing music is Eric Satie’s Jimno Petty No. 1, also arranged and performed by Wu Fei. And our cover art is by Li Yun Fei.Please subscribe wherever you get your podcasts. And if you like what we’re doing, take out a paid subscription at rhymingcaos.com. Salam Boat, thank you so much. Thank you so much.Oh Oh Oh Oh Amen. Love me, me, love me, love, that I do love.

by: https://www.rhymingchaos.com/p/the-end-of-a-mongolian-language-newspaper-1a8?utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web